An Essay by my 18-year-old-self on Gerard Manley Hopkins

A shout out to my grade eleven English teacher, John MacLean

I probably never would have discovered Gerard Manley Hopkins in the first place if it had not been for Mr. MacLean. The best literature teacher I ever had, even including my very small foray into university literature classes. University literature classes make me glad that I am studying translation instead and only have to take four literature classes - although I admit to being glad I took them, and especially enjoyed the medieval French and English literature. I think Mr. MacLean is still teaching English in a High School in Halifax N.S. somewhere.

Some comments before we get started

I'm surprised I even knew what alliteration, repetition and internal rhyme were. I'm guessing I read other people's commentaries on his poetry and they used those terms. I had plenty of time to forget what alliteration was until taking my two English Literature classes this semester. I don't think I had any clue who John Henry Newman was at the time either. It is strange to read myself mention him, now knowing what I did not then. I'm not sure how much of this is just putting together other people's thoughts, and how much are my own thoughts on his poetry. I am guessing it is more the former than the latter. I also don't always stick to the literary present and I am pretty sure that my poetry professor from this semester would be writing comments like "why does this matter?" in the margins because while I am perfectly capable of catching nuances, meanings and metaphors, it seems that I forget to write about what that changes for the reader (or society in general.) Still, it is not a half-bad essay. Which is why I am going to post it here. If you don't know Gerard Manley Hopkins, check him out.

I will add two of my favourite poems by Hopkins at the end of the Essay. The Deutschland is not (and was not) one of my favourites, (by which I do not mean to say that I do not like it, just that I like others better) but when you are limited in research, you do research on the poems that people have written about.

Gerard Manley Hopkins

Jeanne Chabot, June 19, 1990 - For English OAC Class

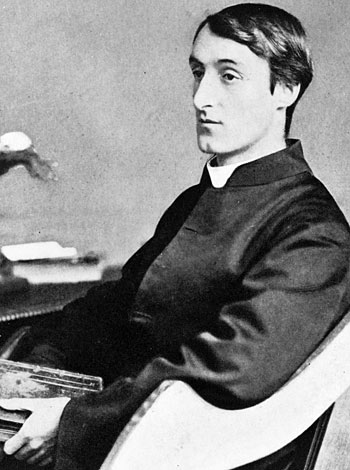

Gerard Manley Hopkins was born July 28, 1844, at Stratford, Essex. He was the eldest of nine children. His father, Manley Hopkins also wrote poems. Hopkins wrote his first poems in grade school. He received a grant to study at Balliol College, Oxford. Here, he wrote poetry while studying classics.

While Hopkins was studying at Oxford, the Oxford movement renewed relationships between Anglicanism and Catholicism. In 1866, Hopkins abandoned his Anglican upbringing and joined the Roman Catholic Church. He was received into the church by John Henry Newman. (Later Cardinal Newman)

Gerard Manley Hopkins left Oxford with an outstanding academic record. In fact, Benjamen Jowett then a lecturer, later the master of the College called him "the Star of Balliol." (1)

Hopkins joined the Society of Jesus in 1868. After entering the Jesuit noviciate, Gerard burned his poetry. He was determined as he said "to write no more, as not belonging to my profession." (2) However, he still kept a journal in which he described in detail his observations of nature and his thoughts on philosophy.

In 1874, Hopkins went to St. Bruno's College at St. Asaph in Wales to study theology. With encouragement from his superior there, he began to write poetry again. It was while he was studying at St. Bruno's that the Deutschland was wrecked. Hopkins was affected by the wreck, as was his superior who said he wished someone would write a poem about it. Hopkins took the hint and wrote "The Wreck of the Deutschland." It is one of his most significant works in which he tried out a new rhythm he had been aching to try before.

In 1877 Hopkins was ordained a priest. He became a professor of Greek at Dublin University in 1884. Hopkins was not happy in Ireland. He was overworked and was in poor health. It was in 1885, that he started writing what are now known as the "Terrible Sonnets" beginning with "Carrion Comfort."

In these Terrible Sonnets, Hopkins shows his depression which came about because of the conflict between the poet in him and his religious vocation. (3) This conflict reflects the ancient tension between the spirit and the flesh. (4) Hopkins had a great desire to express the delights and wonders of God's creation but felt it was not right according to his vocation.

On June 8, 1889, Gerard Manley Hopkins died of typhoid fever in Glasnevin.

After Hopkin's death, Robert Bridges, another poet and good friend of Hopkins', began to publish Hopkins' works. Slowly, they gained popularity and by the 1930s were quite popular.

Gerard Manley Hopkins is a unique poet. He is Victorian but is not like other Victorian poets. He liked to experiment with rhythms. He came up with the idea of "sprung rhythm," where each line contains one stressed syllable and any number of unstressed syllables.

Hopkins turned around the language of poetry. He used old words that people did not use anymore such as dialect words or phrases. He used long forgotten meanings of common words to give his poetry a different twist. He also studied other poetic devices besides the English ones, such as Anglo Saxon and Welsh. He experimented with these devices to express his thoughts and feelings in a unique way that leaves a great impression on the reader of his poetry.

In his poetry, Hopkins uses a variety of literary devices including echo, alliteration, repetition, rhyme and internal rhyme. Alliteration is common in his poetry. For example in line three of "God's Grandeur," he writes "It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil." An example of internal rhyme is found in line six: "and all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil."

Hopkins wrote to Bridges, "No doubt my poetry errs on the side of oddness..." (5) While it may not be odd exactly, it is true that his poetry is definitely unique.

Hopkins' poems express deep personal experiences, emotions and his delight at the Grandeur of God, His greatness and splendour. He was enthralled by the beauty of the created world. For example, in "Pied Beauty" he expressed his joy "in all things counter, original, spare, strange." (6)

Hopkins emphasized the inscape of every object. He believed that everything in nature has its own elusive "selfness." (7) Instress and inscape underlie his poetry. Both of these terms were Hopkins' coinages. Inscape is the essential inner nature of a person or object, while instress is the divine force which creates the inscape of an object or event.

Hokins' poetry combines the subtlety of perception, force of intellect and intensity of religious feeling. It contains imagination, observation, deep feeling and intellectual depth. (8)

Coventry Patmore wrote about Hopkins: "There was something in his words and manners which were at once a rebuke and an attraction to all who could only aspire to be like him." (9)

"The Wreck of the Deutschland"

In the poem "The Wreck of the Deutschland," written by Gerard Manley Hopkins, God is an important factor. In the first part, Hopkins talks about his faith in God. In the second part, he applies his faith in God to the wreck of the Deutschland, using symbols, personifications and irony.

In the first stanza of Part The First, Gerard Manley Hopkins talks about how God made him then goes on to say: "And does thou touch me afresh?/Over again I feel they finger and find thee." (10) Here is a unique way of saying God is still moulding him; shaping him. Hopkins puts words together so well that he gives them an impressive meaning that lasts.

Hopkins was a staunch Catholic and in "The Wreck of the Deutschland," Catholic symbols make their way to the surface over and over. In stanza three, Hopkins talks about Holy Communion as he says: "And fled with a fling of the heart to the heart of the host." (line 21) Holy Communion is a very important symbol in the Catholic Church. In fact, it is more than a symbol, it is a relationship with God.

In stanzas six and seven, Hopkins makes sure that we realize that suffering does not make God happy. Once again he expresses this so well as he says: "Not out of his bliss springs the stress felt [...] Nor first from Heaven (and few know this.)" (lines 41-43) Jesus suffered too and here, another major theme in the Catholic faith surfaces as Hopkins talks about "The dense and driven Passion and frightful sweat." The Passion of our Lord is a much-meditated subject in the Church.

In the first stanza of Part the Second, stanza eleven, Death is personified. Death speaks saying "'Some find me a sword; some/The flange and the rail; flame,/fang or flood.'" (lines 81-83) Here Hopkins reminds us that someday we will all die.

Irony is portrayed in stanza thirteen. Instead of staying in port, the ship headed out into the middle of a snowstorm as Hopkins puts it: "Into the snow she sweeps,/hurling the haven behind." (lines 97-98) The shipwreck might never have happened had they not ventured out anyway.

In stanza fifteen, Hope is personified in a very unique way. Hopkins adds a twist to the character of Hope in the way he describes her:

Hope had grown grey hairs,Hope had mourning on.Trenched with tears, carved with cares,Hope was twelve hours gone. (lines 113-116)

This is a great portrayal of Hope. You can almost see her, bent over in dark clothes, mourning, in the middle of a storm, while everyone has given up.

As the ship started to go down, a Mother Superior took over in the panic. She and four other nuns stood in a circle holding hands as she called "O Christ come quickly." This is a recurring theme in the rest of the poem, as Hopkins was obviously impressed by her faith. Hopkins describes the event: "Till a lioness arose breasting the babble/A prophetess towered in the tumult, a virginal tongue told." (lines 135-136) Again he talks of her crying out in stanza nineteen as he says: "Sister, a sister is calling/A master, her master and mine! [...] and the call of the tall nun/to the men in the tops and the tackle rode over the storm's brawling." (lines 145-146) In stanza thirty-one Hopkins compares her call to a bell summoning others to God as he says: "the breast of the /Maiden could obey so, be a bell to, ring of it, and/Startle the poor sheep back! Is the shipwreck then a harvest, does/Tempest carry the grain for thee?" (lines 246-248)

In stanzas twenty-two and twenty-three, the number five is a symbol. Hopkins talks about the five wounds of Christ as he says: "Five!/The finding and sake/and cipher of suffering Christ." (lines 170-171) He talks about the cinquefoil which is a five-leaved flower or architectural ornament with five points. He talks of Saint Francis who received the sacred wounds of Christ as he says: "Joy fall to thee, Father Francis, [...] with the gnarls of the nails in thee, niche of the lance," (lines 178 and 180) and he talks of the five sisters in the wreck.

In stanza thirty, Hopkins compares the nun's death with the feast of the Immaculate Conception as he says:

What was the feast followed the nightThou hadst glory of this nun? --Feast of the one woman without stain.For so conceived, so to conceive thee is done; (lines 236-239)

In stanza thirty-one, Hopkins' faith in God rises to the surface once more. When he says: Well she has thee for the pain, for the/Patience; but pity the rest of them!" (lines 242-243) he shows his own total dependence on God as well as the nun's.

In stanza thirty-five, the last stanza in the poem, Hopkins expresses a desire for everyone to know Christ as he does. He asks the nun to send "Our King back, oh, upon English souls!" (line 276) At the end, in his own special, unique way, Hopkins talks of the fire of his faith, as he says: "Our hearts' charity's hearth's fire, our thoughts' chivalry's throng's Lord." (line 281)

"The Wreck of the Deutschland" is a touching story of faith in times of deepest trouble, joy in times of deepest sorrow and hope in times of deepest despair. Gerard Manly Hopkins' sensitivity, creativity, imagination, and personal faith and conviction give the poem a life of its own and a certain touch no one else could ever hope to attain.

Endnotes:

1. John Cowie Reid, "Gerard Manley Hopkins" Encyclopedia Britannica, (Helen Hemmingway Benton, 1976) 8:1070-1071.

2. Ibid

3. Ibid

4. Benjamen Evan Owen, "Gerard Manley Hopkins" Encyclopedia Britannica, (William Benton, 1962) 11:737-738.

5. David Daiches, "Gerard Manley Hopkins" The Norton Anthology of English Literature, (W.W. Norton and Co. 1962) pp 1235-1239.

6. Gerard Manley Hopkins, Victorian Poetry and Poetics, (Houghton Mifflin Co.) p. 81.

7. Reid, "Gerard Manley Hopkins" Encyclopedia Britannica, (1976) 8:1070-1071

8. Ibid

9. Ibid

10. Hopkins, Victorian Poetry and Poetics, pp. 72-80, lines 7-8. All subsequent references will be made to this edition.

Bibliography:

Daiches, David "Gerard Manley Hopkins" The Norton Anthology of English Literature, United States:

W.W. Norton and Co. 1962. pp 1235-1239.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley Victorian Poetry and Poetics - Second Edition, New York: Houghton Mifflin

Co. 1968

Owen, Benjamen Evan "Gerard Manley Hopkins" Encyclopedia Britannica, Chicago: William Benton.

1962. 11:737-738

Reid, John Cowie "Gerard Manley Hopkins" Encyclopedia Britannica, Toronto: Helen Hemmingway

Benton. 1975. 8:1070-1071

"Wreck of the Deutschland, The" Encyclopedia Britannica, Toronto: Helen Hemmingway Benton.

1976. X Addenda: 159

The Windhover

To Christ our Lord

I caught this morning morning's minion, king-

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate's heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, -- the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, plume here

Buckle! ad the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my Chevalier!

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash-gold vermilion.

1877

Pied Beauty

Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

1877

Comments

Post a Comment